Leave Me Alone, I Have Work to Do: The Story of Barbara McClintock

Barbara McClintock possessed perhaps the most important qualities to work in science and gain world recognition: absolute self-confidence and dedication. Having discovered one of the most mysterious structures in the genome in the middle of the last century, she announced the existence of transposons – jumping genes that randomly change their position – long before the era of molecular genetics. And for many years, being obstructed and persecuted, she did not allow herself to doubt her work.

Barbara McClintock preferred reading and gardening since childhood: the future great scientist became interested in biology in high school. After school, she wanted to continue her education by entering the university, but the First World War was going on, in which her father served as a military surgeon, and the family was in poverty. Barbara was forced to work.

However, this did not kill her love for science — Barbara signed up for the nearest library and read almost all her free time. After the war, in 1919, Barbara entered Cornell University.

At the university, Barbara met her main subject — corn, and her main passion — genetics, a science that was just emerging, promising amazing discoveries in the coming years. By her own admission, plants became her family. While no one interfered with her study of the first, a problem arose: the genetics department did not accept women. Well, this did not stop Barbara — she brilliantly graduated from the Department of Botany.

McClintock in 1923, when she graduated with a bachelor's degree from Cornell University. Source.

After university she worked at the University of Missouri in the 1940s. There she discovered the existence of ring chromosomes and a nucleolus. However, these discoveries did not force the scientific community to treat her — a woman — better. Barbara was not allowed to attend meetings, her opinions were not listened to, and after some time they stopped inviting her to department meetings altogether.

But she seemed to be simply oblivious to the difficulties that were piling up on her path, and her career was still going uphill. As always, there were people who sincerely supported her on this path: one of them was Milislav Demerek, chief of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York, who gave her the opportunity to do science, providing a permanent job. This allowed Barbara to stop thinking about her daily bread, devoting herself entirely to what she loved — corn.

Here, at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Barbara made the greatest discovery of her life: she identified transposons jumping around the genome. Unlike most scientific ideas observed in practice, she hypothesized their existence theoretically, based on indirect data. At some point, while sorting through corn kernels, she noticed a strange phenomenon: some properties were manifested in plants that did not have the genes responsible for these properties, and they were manifested in spots, like a mosaic. Barbara was a scientist, which meant she was curious: she immediately began to figure out what was actually happening.

After some time, she came to an amazing result: the corn genome contains jumping genes that change their location at their own whim and affect other genes and their manifestations. She called these amazing elements a dissociation element and an activator, in honor of their ability to negatively or positively affect other genes.

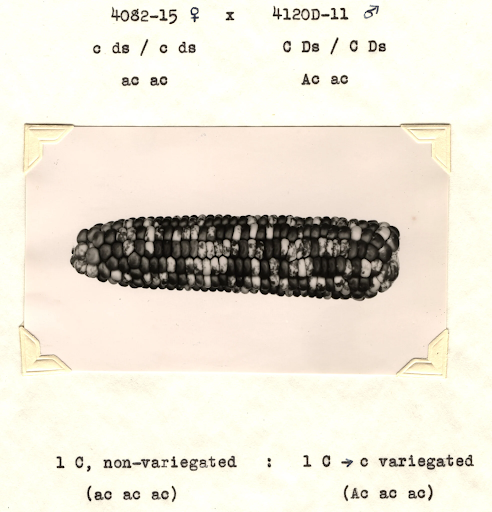

Corn mosaicism - grains are different, although genetically they should be the same.

The dissociator and activator jumped randomly around the genome – exactly how was only discovered three decades later – and, when they entered a gene, they completely changed its expression. Barbara demonstrated the work of these elements using the example of the synthesis of anthocyanins, plant pigments, in corn. If the gene contained a dissociator with no copies of the activator, then the grain did not synthesize pigment. If the grain contained only one copy of the dissociator and several copies of the activator, a small amount of anthocyanin was synthesized. If the activator was fully present, while the dissociator was absent, then the grain was colored more than all the previous ones. The copies of the dissociator and activator could jump randomly, forming a wide variety of combinations.

Barbara's idea of jumping genes was elegant and explained the genetic mystery quite well: why, with a single genetic code, different genes could manifest themselves in different parts of the body. On the other hand, it sounded extremely strange: jumping genes?! Moreover, Barbara said directly: if you approach the issue correctly, the genome can be regulated!

"Over the years I have found that it is difficult if not impossible to bring to consciousness of another person the nature of his tacit assumptions when, by some special experiences, I have been made aware of them. This became painfully evident to me in my attempts during the 1950s to convince geneticists that the action of genes had to be and was controlled".

Her first report on transposons was met with stony silence. Some simply chose not to react to her bold statements, while others openly declared Barbara crazy. But the words of her colleagues meant nothing to her — she was good at concentrating only on what was in her own head.

Publications about amazing genes were met with indignation and controversy at best, and complete silence at worst. In an extensive textbook on genetics published in the 1960s in the US, Barbara was not given a few words in the chapter on the history of genetics, although out of 17 major discoveries in plant genetics made in the 1930s, 10 belonged to her.

Did this silence stop her? No. She had corn, loyal assistants, colleagues and students, and most importantly, a love for science and scientific research.

The years passed, and 20 years after the publication of the first hypothesis on transposons, already in the late 1960s, transposons were discovered in bacteria, and then in yeast. The idea of a controlled genome was spreading more and more throughout the scientific community. Not immediately, but the scientific world realized that McClintock was right. The transposase enzyme, which allows transposons to jump around the genome, was found, and a precise link was established between transposons and the genetic variability of organisms. By the 1970s, it became clear that Barbara, in essence, defined modern genetics — and a stream of public recognition poured in her direction. The President of the United States personally presented her with the National Medal of Science in 1971. TV shows were made about her, books were written about her, and she was invited to lecture at the country's leading universities. All this affected her little — she was still interested in her cornfield and her experiment.

Barbara worked at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory for another 10 years, continuing to teach students until her death at the age of 90. Plants were her inspiration until the end of her life.

What You Can Learn from Barbara McClintock

The scientific community declared her crazy, but her independence from other people's opinions helped her endure years of persecution. After receiving the Nobel Prize, looking back, Barbara McClintock will say:

"Over the many years, I truly enjoyed not being required to defend my interpretations. I could just work with the greatest of pleasure. I never felt the need nor the desire to defend my views".

"They said I was crazy — absolutely mad. But when you know you are right you don't care".

After her death one of the buildings of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory was named in Barbara's honor, and an award was established in her name for students. McClintock's example continues to inspire women around the world: everyone can achieve greatness, the main thing is to remember that no matter what others say, "when you know you are right you don't care".

What Helped Her Continue Her Work

Perhaps the easiest way to answer the question of what kept her going is that she really loved science and her corn.

“I know every plant in the field”, — she said. “I know them intimately. And I find it a great pleasure to know them.”

In 1983, 81-year-old Barbara McClintock, upon learning that she had won the most prestigious prize in science, smiled and said, “Thank you. That’s very sweet. Thank you for the prize. You know, I don’t really need it. You didn’t believe me before, now you do – good. Leave me alone, I have work to do.”

About the Author: Zoe Chernova is a science journalist and communicator with a background in biochemistry. She studied reactive oxygen species, and after leaving the Academia, she started to write about modern science, unusual phenomena, and female scientists. She is especially interested in animal culture and runs a popular science newsletter Look What I Found in Science.